. . .บ่อยครั้งที่คุณงามความดีมันพัวพันกับการใจจดใจจ่อรอห้วงเวลาหนึ่งหลังมรณภาพ

ห้วงเวลาที่เราสามารถม้องย้อนรำลึกถึงปัจจุบันกาลด้วยอารมณ์เป็นกลางเข้าขั้นไม่แยแส ด้วยไมตรีจิตติดตรึงใจของความตายไมเคิ้ล ซิสโก้

แพทย์แผนใหม่ของหมอบอนดี

ประมาณตีหนึ่งตีสองของเช้าวันที่ 20 กันยายน 2563 หลังจากพิธีกรกล่าวลาเดินลงจากเวทีหลัก ณ การชุมนุมข้ามคืนที่ท้องสนามหลวงอันเป็นการชุมนุมประท้วงเพื่อประชาธิปไตยไทยมหึมาครั้งแรกที่มีผู้เข้าร่วมนับแสนในรอบหลายปี ภาพยนต์สารคดีดีกรีโดนรัฐแบนเรื่อง ประชาธิปไตยหลังความตาย ผลงานผู้กำกับลี้ภัย เนติ วิเชียรแสน ก็ได้ฉายบนจอกลางเวทีใหญ่ยักษ์เป็นครั้งแรกในประเทศตั้งแต่ปล่อยฉายเมื่อปี 2549 เนื้อหาของภาพยนตร์ดำเนินตามบทบรรยายของวิญญาณตนหนึ่ง เป็นเงาของชายไร้นามไร้ซึ่งพิกัดใดๆ นอกจากเรื่องที่เขาเล่าให้คนดูฟัง เรื่องราวที่แม้แต่เขาก็ไม่มีบทบาทให้เล่น เรื่องราวที่เดินไปข้างหน้าแบ่งเป็นบทๆ ตามดีกรีความโลกาพิบัติภายใต้กระแสเสรีนิยมสมัยใหม่วัดจากโมเดลโทรศัพท์มือถือยี่ห้ออีโฟนรุ่นใหม่ที่ออกมาเรื่อยๆ เทียบขนานกันไปกับจำนวนครั้งการรัฐประหารและจำนวนคนเสื้อแดงตายในราชอาณาจักรไทยระหว่างปี 2547 – 2559 เจ้าเงามืดที่ติดอยู่ในภูมิภาพเป็นฉากๆ เปลี่ยนไปเรื่อยจากข้างกองไฟในความมืดสนิทเป็นชายหาดเงียบสงบเป็นเนินทะเลทรายไกลสุดลูกหูลูกตาเหมือนเวียนว่านอยู่ในลิมโบ้กึ่งนรก ก็ทำได้แต่เดินตามและพูดพร่ำให้เงามืดอีกตนหนึ่งฟัง เงามืดของลุงนวมทอง ไพรวัลย์ ผู้มาและจากไปก่อนกาล ลุงผู้ขับรถแท๊กซี่โตโยต้าโคโรล่าเครื่องมือหาเลี้ยงชีพตนพุ่งเข้าชนรถถังเอ็ม 41 วอล์คเก้อ บูลด็อก เครื่องมือหาเลี้ยงอำนาจของกองทัพบกและรัฐบาลจากการรัฐประหารของพลเอก สนทิ บุนยรัตนกลิน เมื่อ 30 กันยายน 2549

สำหรับคนนอนสนามหลวงหลายคนในคืนนั้น ครั้งนี้อาจเป็นครั้งแรกที่ได้ยินชื่อลุงนวมทองและรู้สึกจับใจกับความทุ่มสุดตัวของคุณลุง สำหรับคนอื่นๆ อีกจำนวนหนึ่ง การขัดขืนครั้งสุดท้ายของลุงต่อคำพูดเบ็ดเสร็จเด็ดขาดของรัฐบาลรัฐประหารที่ว่า ‘ไม่มีใครมีอุดมการณ์มากขนาดยอมพลีชีพได้’1คำพูดของ อัคร ทิพโรจน์ รองโฆษกปากหมาของคณะรัฐประหารหัวควยในเวลานั้น. เป็นจุดจบที่คุ้นเคยกันอยู่แล้ว จุดจบที่ยิ่งใหญ่ถึงขนาดมีคนพยายามแปลความตายนี้ทั้งจากจิตสำนึกแห่งการปฏิวัติและจากจิตสำนึกสลิ่ม ได้ยินบ่อยๆ เช่น ‘ลุงเป็นวีรบุรุษประชาธิปไตยผู้มาก่อนกาล!’, ‘ลุงแกไม่น่าฆ่าตัวตายเลย ใครจะอยู่ดูแลครอบครัวที่ทิ้งไว้ล่ะ’, และอื่นๆ การพูดเข้าข้างผู้เป็นอื่นเช่นนี้ไม่สามารถทำให้เราเห็นอุบัติการณ์และตัวของลุงนวมทองเกินกว่าเป็นวัตถุทางประวัติศาสตร์ได้ เป็นได้แค่ข้อเท็จจริงทางนามธรรมตัดขาดจากความจริงแท้ที่แท้จริง ฉะนี้ข้าพเจ้าจึงอยากชวนให้ทุกคนกลับมาอ่านซิกมุนด์ ฟรอยด์กันอีกครั้งรอบนี้แบบปลาดปลาด ถ้าเรามองจากมุมแยกกันสองมุมจากอัตตะบางประเภทจะพบว่าแนวคิดเรื่องเด๊ดไดรฟ์ (ที่คำแปลภาษาไทยไม่ค่อยรื่นหูว่า แรงผลักดันแห่ง/สู่ความตาย) และความตายของลุงนวมทองมันดูไม่อาจจะเข้าใจได้ แต่พอเอาสองอย่างนี้มาพิจารณาพร้อมกันในภาพเดียวกัน เสริมด้วยการอ่านความวิตกจริตเชิงคอสมิกอันเป็นหัวใจสำคัญของปรัชญาปลาดคดี เราก็จะได้ภาพรวมที่ไม่สมบูรณ์ ขาดๆหายๆ เป็นรูปเป็นร่างพอเห็นเค้าโครงความจริงอะไรบางอย่าง

นรกส่งกลับมาเกิด: พุทธองค์ดายทไวซ์

ประชาธิปไตยหลังความตาย ทั้งในเชิงอารมณ์วิธีการและโครงสร้างเรื่องเล่า ทำให้คนดูหวนนึกตลอดเรื่องกลับไปถึงประโยคนึงที่ลุงนวมทองพูด ‘ชาติหน้าเกิดมาคงไม่พบเจอการ [รัฐประหาร] อีก’2เป็นคำสั่งลาครอบครัวของลุงแกในจดหมายลาตาย. เจ้าตัวบรรยายเรื่องก็ได้แต่พูดออกมาเหมือนจะสื่อสารกับคนตายที่ตอบไม่ได้ ลอยขวดส่งสาสน์จมลงสู่ทะเลแห่งความจริงแท้อันเป็นผืนแผ่นความบอบช้ำไร้ชายฝั่งอื่นว่า ‘นี่ถ้าลุงได้เข้าสู่วงจรแห่งการเวียนว่ายตายเกิดทันทีหลังที่ตายไป ตอนนี้แกคงเป็นเด็กอายุประมาณสิบขวบแล้ว’ แล้วอะไรคือ afterlife? อะไรคือห้วงเวลาหลังความตายนี้ที่ลุงนวมทองผู้กลับชาติมาเกิดจะได้ลิ้มรสประชาธิปไตยฉบับที่แกไม่ได้มีโอกาสสัมผัสในชาติที่แล้ว? คาซุชิเกะ ชิงกู กับ เท็ดซึโอะ ฟูนากิ ช่วยกันเขียนบทความหนึ่งในวารสาร ทฤษฎีและจิตวิทยา3Kazushige Shingu; Tetsuo Funaki (2008), ‘Between Two Deaths’: The Intersection of Psychoanalysis and Japanese Buddhism, Theory and Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354307087885. โยงใยเรื่องวงจรการเวียนว่ายตายเกิด, ชีวิตหลังความตาย, และสังสารวัฏ เข้ากับสิ่งที่ทั่นนายแพทย์ซิกิซมุนด์ ชโลโม ฟรอยด์ เรียกว่าเด๊ดไดรฟ์ ชิงกูกับฟูนากิอ่านจิตวิเคราะห์ควบคู่กับคำสอนและธรรมเนียมปฏิบัติของพุทธหลายๆ นิกายในประเทศอดีตจักรวรรดิญี่ปุ่น โดยชี้เน้นให้เห็นฟีเจ้อทางโครงสร้างสำคัญสองอันที่มักถูกมองข้ามในนิยามของชีวิตหลังความตายของศาสนาเทวนิยม คือ มันมีความตายเกิดขึ้นอีกครั้งหนึ่งหลังจากความตายทางกาย และสภาพการดำรงอยู่ของชีวิตหลังความตายไม่ได้เป็นไปตามลำดับเวลาอยู่ระหว่างความตายครั้งแรกและครั้งที่สองอย่างที่สำนึกสามัญเข้าใจกัน เราสามารถเข้าใจเด๊ดไดรฟ์มุมหนึ่งผ่านพลวัตของอัตตะในโครงสร้างนี้

ลองสมมติบทสนทนาเชิงเลนินนิสท์ที่เราก็คงเคยได้ยินกันบ้างล่ะ ดังนี้

ข้าราชการอาวุโสคนหนึ่งเดินมาเจอผู้ร่วมงานอีกสองคนกำลังถกเถียงกันอย่างดุเดือดเรื่องการใช้กำลังเกินจำเป็นของรัฐในการสลายการชุมนุมที่เกิดขึ้นเมื่อวาน ขรก.อาวุโสได้ยินดังนั้นก็ชูผายมือขึ้นสองมือระดับศรีษะ ส่ายหัวนิดหน่อยแล้วพูดออกมาได้ว่า “นี่ พี่ว่าเราไม่ควรพูดเรื่องการมงการเมืองในตึกนี้ตอนใส่เครื่องแบบนี้อยู่นะ เราเป็นข้าราชการก็ต้องเป็นกลางทางการเมือง พี่ก็มีครอบครัวลูก/ผัว/เมีย/พ่อแม่แก่เฒ่าต้องดูแลเค้าก็ต้องพึ่งพาเงินเดือนและสิทธิเบิกข้าราชการของพี่ พี่ไม่อยากเสียสิทธิตรงนี้ โดนงดบำนาญกับเรื่องไม่เป็นเรื่อง พอเกษียณแล้วพี่ก็แค่อยากไปเที่ยวตกปลา แทงสนุ๊กเรื่อยเปื่อยขอแค่นั้นก็พอ”

สิ่งที่เรียกว่าเด๊ดไดรฟ์ในทฤษฎีจิตวิเคราะห์มันก็อยู่ในเนื้อหาคำพูดของ ขรก.อาวุโสตรงประโยคท้ายนี่แหละ อยู่ในสภาพ indefinite postponement (ภาวะการผัดวันประกันพรุ่งแบบไม่มีกำหนด) และการทำหรือการเกิดซ้ำๆ ซากๆ อยู่ในคำพูดที่ว่าถึงเวลาจุดหนึ่งในอนาคตอันคลุมเครือที่ในที่สุดผู้พูดก็จะสามารถมีชีวิตที่กูอยากจะมีได้แล้ว ชีวิตที่กูจะทำกิจกรรมหรืองานอดิเรกอะไรก็ได้ที่จริงๆ แล้วมันมีเนื้อหาเพียงคงไว้ซึ่งและผลิตซ้ำโครงสร้างนี้ในปัจจุบันนิรันดร์กาล4ทุกวันนี้เราคงอาจจะเคยได้ยินปรากฏการณ์ทางสังคมที่เรียกว่า ฮิคิโคะโมริ (Hikikomori) หรือปรากฏการณ์ที่คนมีพฤติกรรมแยกตัวออกจากสังคมที่เริ่มจะลามไปทั่วภูมินาครในกลียุคทุนนิยมตอนปลายของเอเชียตะวันออก ข้อขัดแย้งในกรณีนี้เห็นได้ชัดเพราะอัตตะเลือกเองที่จะไม่เป็นส่วนหนึ่งในกระบวนการผลิตซ้ำกำลังแรงงาน เลือกที่จะถอนตัวจากชีวิตสังคมเพื่อที่จะสามารถจินตนาการชีวิตประเภทที่อัตตะสามารถอยู่ได้. ฟรอยด์เห็นว่า pleasure principle (หลักการทำงานของความสุข) หรือแรงผลักดันที่ขับให้อัตตะคลี่คลายปมความตึงเครียดภายใน ท้ายที่สุดแล้วมันทำงานเป็นเบี้ยล่างให้กับ ‘ฟังก์ชั่นๆ หนึ่ง. . .แต่เราสังเกตได้ว่าฟังก์ชั่นที่เรานิยามเป็นรูปเป็นร่างได้นี้ก็จะเข้าไปมีส่วนร่วมในแนวโน้มหนึ่งที่มีอยู่ในทุกสรรพสิ่งมีชีวิต — นั่นก็คือแนวโน้มการกลับสู่ความสงบของอนินทรียภพ’5จากบทความยาว สุดขอบฟ้าของความสุข บทย่อยที่ 7 ของทั่นนายแพทย์ซิกิซมุนด์ ชโลโม ฟรอยด์ ใครที่คุ้นเคยกับงานของโรเบิร์ต เพียร์สิก ก็อาจจะจำได้ทันทีว่า เอ๊ะ! ไอ้แนวโน้มนี้มันคือที่เพียร์สิกเรียกว่า การถดถอยกลับสู่รากเหง้า ‘อันผิดศีลธรรม’ ของสรพพสิ่งชีวะ/อินทรีย์กลับสู่อนินทรียสารนี่นา อยากรู้เหมือนกันว่าอภิปรัชญาเชิงคุณภาพของเพียร์สิกจะตอบโจทย์คลี่คลายข้อขัดแย้งภายในอัตตะนี้ที่อยู่นอกกรอบเบ็ดเสร็จทางความคิดของอภิปรัชญายังไง. ถ้าคิดตามตรรกะนี้ก็จะเห็นว่าชีวิตหลังเกษียณที่ ขรก.อาวุโสคนนี้จินตนาการไว้ซะดิบดี มันไม่ใช่วัตถุที่ปลายสายรุ้งของเรื่องราวชีวิตการทำงานของ ขรก.คนนี้ที่หลอกตัวเองเรื่อยมา แต่การที่จะได้ชีวิตเสพสุขนี้มาจริงๆ แล้วคือการที่จะได้มาซึ่งชีวิตที่สามารถทำความเข้าใจยอมรับกับความตายทางกายอันเป็นความตายครั้งแรกของมนุษย์ ไม่ว่าอัตตะจะรู้ตัวหรือไม่ว่าตัวเองเป็นส่วนหนึ่งในกระบวนการนี้ และแน่นอนมันไม่มีการันตีว่าโครงสร้างนี้จะหายไป ไม่ผลิตซ้ำตัวมันขึ้นมาอีกในรูปแบบที่เห็นได้เป็นอย่างอื่น เช่น เริ่มเคร่งศาสนาเข้าวัดเข้าโบสถ์บ่อยในยามแก่เฒ่า หรือหางานอดิเรกใหม่ๆ ทำเพิ่มเรื่อยๆ และอื่นๆ แม้ว่า ขรก.ผู้นี้จะเกษียณอายุเรียบร้อยไม่มีปัญหาโดนงดบำเหน็จบำนาญใดๆ

ไอ้การพยายามทำความเข้าใจยอมรับความตายครั้งแรกที่ว่ากันจริงๆ มันก็เป็นความตายครั้งเดียวอะนะ คือเป้าหมายของศาสนาแทบจะทุกศาสนา แต่มีศาสนาเดียวที่บรรยายโครงสร้างของชีวิตหลังความตายได้ถูกต้อง นั่นก็คือศาสนาพุทธดั้งเดิมตามคำสอนของพระโคตมพุทธจ้าวที่พยายามช่วยให้อัตตะปลดปล่อยตนเองให้หลุดพ้นจากภาษาที่แบ่งอัตตะให้เลือกไม่ได้ว่าความตายมันเป็นสิ่งน่าปรารถนาหรือไม่ พระโคตมพุทธจ้าวผู้มีวิชาหยั่งกะว่าอ่าน จ๊าก! ละคานมาชิงตายครั้งที่สองคือการฆ่าความทุกข์ที่เกิดจากมฤตภาพอันเป็นสัจธรรมของชีวิตให้ตาย ก่อนที่จะตายครั้งแรกซะอีก เป็นการกลับหัวหางและยุบทำลายมิติที่สี่ จนได้มาเป็นองค์ความรู้ใหม่ว่าเวลาที่เรามีใช้ในโลกหน้ามันจำกัดและจบลงก่อนที่มันจะเริ่มซะด้วยซ้ำ

แน่นอนว่า ประชาธิปไตยหลังความตาย ไม่ใช่เรื่องราวของชีวิตหลังความตายของลุงนวมทอง แต่เป็นของคนดูเอง เพราะความตายครั้งที่สองของลุงนวมทองได้ผ่านพ้นไปแล้ว เห็นได้จากการยอมรับแบบจำนนต่อความคิดเรื่องการกลับชาติมาเกิดใหม่ในข้อความสุดท้ายของลุง เงามืดผู้บรรยายกับคนดูต่างหากที่ยังติดอยู่ในสังสารวัฏ รอคอยการมาของประชาธิปไตยเหมือนกับที่ ขรก.อาวุโสรอชีวิตหลังเกษียณ วนเวียนอยู่กับมันได้ด้วยการทำซ้ำคิดซ้ำอะไรบางอย่างอยู่ตลอดกาล

อมตภาพทางนามธรรม

อ่านมาถึงตรงนี้ทั่นผู้อ่านก็อาจจะมีคำถามอยู่ในใจว่า แล้วลุงนวมทองแกบรรลุนิพพานตอนไหน? ดูจากความทรงพลังของอุบัติการณ์การขับรถพุ่งชนรถถังของแก ก็เป็นไปได้ว่าแกบรรลุแล้วก่อนจะก้าวขึ้นรถแท๊กซี่หรือหลังจากรอดตายจากการชนในวันนั้น ข้าพจ้าวคิดว่าเราไม่ต้องมาชี้ชัดหรอกว่าลุงนวมทองหรือพุทธจ้าวบรรลุนิพพาน ณ ที่ไหน วันไหน เวลากี่โมงกี่ยาม นั่นก็เพราะอัตตะที่กำลังติดอยู่ในวงเวียนเด๊ดไดรฟ์จะประสบรับรู้ปัจจุบันกาลเหมือนกับตนเองเป็นอมตะ กล่าวคืออัตตะเหล่านี้รับรู้ว่าชีวิตหลังความตายมันอยู่ในอนาคตที่มาไม่ถึง ตรงกันข้ามกับความเข้าใจผิดของอุดมการณ์จิตวิทยานิยม เด๊ดไดร์ฟไม่ใช่สิ่งที่รุนแรงเลย หลักการของมันไม่ได้วางอยู่ตรงกันข้ามกับหลักการทำงานของความสุข แต่อยู่เลยเส้นขอบความเป็นไปได้ของความสุขออกไปต่างหาก เมื่อเราถูกความสุขรีดเร้นจนหมดเปลือกแล้ว กากเหลือที่ตกค้างอยู่ไม่ใช่ความรุนแรงแต่เป็นความสลดหดหู่ ข้าพจ้าวจึงมีความเห็นว่าเราไม่ควรอ่านความรุนแรงในอัตวินิบาตกรรมเชิงสัญลักษณ์ซะด้วยซ้ำ เพราะว่าความรุนแรงนี่แหละคือคำที่รัฐไทยใช้เป็นข้ออ้างแบน ประชาธิปไตยหลังความตาย เพื่อไม่ให้ประชาชนต้องเผชิญหน้ากับความบอบช้ำอันจริงแท้

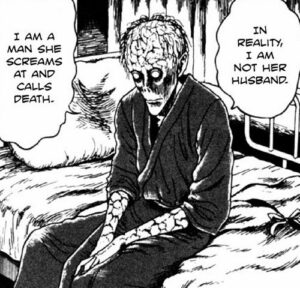

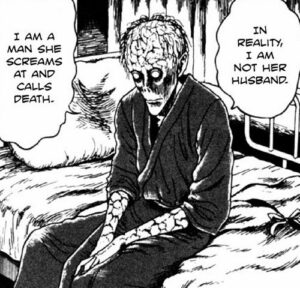

เช่นกัน เมื่อเราอ่านผ่านภาพอันน่าสะพรึงและกลยุทธ์การประพันธ์ตามขนบเรื่องแนวสยองขวัญเราก็จะพบคาแรกเตอร์ที่แท้จริงของวรรณกรรมแนวปลาด ตัวอย่างที่เห็นได้ชัดเลยคือผลงานมังงะของ อิโต้ จุนจิ ที่วาดรูปออกมาได้ซะขยะแขยงพิลึกเกินกว่ารสนิยมของปลาดชนบางคนอาจรับได้โดยเฉพาะพวกคลั่งเลิฟคราฟท์อย่างเดียว6 การถกเถียงกันเรื่องคุณค่าของงานทัศนศิลป์ของอิโต้เป็นส่วนหนึ่งของการถกเถียงที่ใหญ่กว่าในประเทศไทยเรื่องการนิยามปลาดคดีในบริบทของเรื่องเหนือธรรมชาติไทย เมื่อสิงหาคม พ.ศ. 2563 ที่ผ่านมา หนึ่งในกฏที่ชอบใช้กันบ่อยๆ เพื่อแยกเรื่องสยองขวัญแนวเลิฟคราฟท์ออกจากเรื่องสยองขวัญทั่วไปคืออย่างแรกไม่ได้พึ่งพาความน่ากลัวทางทัศนะเป็นเนื้อหาหลักของความกลัว จากกรณีของอิโต้ก็เห็นอยู่ว่ากฎนี้ยังมีวิชาไม่พอ ประเด็นไม่ได้อยู่ที่ว่าการสื่อออกทางทัศนะมันจะมากเกินรสนิยม ประเด็นมันอยู่ที่ว่าต่อให้สื่อออกมาเป็นผีหลอกสัตว์ประหลาดน่าขยะแขยง ตุ้งแช่ ขนาดไหนมันก็ไม่พอที่จะสื่อเนื้อหาที่อยู่เลยขอบเขตของตัวบ่งชี้ที่เรียกว่า “ความกลัว” ได้. ผลงานของอิโต้เช่น ก้นหอยมรณะ และ ปลา เป็นที่รู้จักกันดีในความที่ภาพวาดมันน่าขยะแขยงชวนคลื่นไส้และหวาดวิตกแบบอวัตถุ7ในความเห็นของข้าพจ้าว เหตุที่งานของอิโต้มันมีพลังก็เพราะมันมีครบทั้งสามองค์ประกอบที่เกี่ยวข้องกับความประสาทที่ฟรอยด์พูดถึงใน สุดขอบฟ้าของความสุข คือ ความหวาดหวั่น (apprehension) ว่าเปิดหน้าต่อไปแล้วจะเจอภาพอันน่าสยดสยองอะไร, ความหวาดกลัวแบบตุ้งแช่ (fright) ที่ถึงแม้จะพอรู้อยู่แล้วว่าจะเจออะไรแต่ก็ไม่พร้อมที่จะเผชิญหน้ากับมันบนหน้าหนังสืออยู่ดี, ความหวาดกลัวแบบคงตัว (fear) ที่ถึงแม้คนเขียน คนวาด จะเปิดเผยสิ่ง/สัตว์ปลาดให้รู้เห็นแล้ว แต่ก็ยังมีโมเมนตั้มความสยองผลักส่งมันไปข้างหน้าได้เรื่อยๆ. ส่วนตัวข้าพจ้าวคิดว่าอัจฉริยภาพปลาดของอิโต้เปล่งประกายทั่วหล้าสว่างที่สุดในเรื่องสั้น ฝันยาว ในรวมเล่ม คลังสยอง เล่ม 9 เนื้อเรื่องมีอยู่ว่า หมอคุโรดะ ดูแลอาการของผู้ป่วยสองคน มามิผู้ป่วยเป็นโรคอะไรไม่ระบุแต่ไม่ร้ายแรงเท่ากับที่เธอหวาดหวั่นความตายจากโรคนี้ และอีกคนนายมุโคดะ ผู้มีอาการรับรู้ว่าเวลาที่อัตตะตนเองใช้ในความฝันแต่ละคืนมันเริ่มนานขึ้นนานขึ้นเรื่อยๆ ตอนแรกมุโคดะรับรู้ใช้เวลาในความฝันคืนหนึ่งเท่ากับหนึ่งปี ยิ่งเวลารับรู้นี้ยิ่งยาวขึ้นไปพร้อมๆ กับเนื้อหาความฝันที่ปลาดขึ้นตามอัตราส่วนเดียวกันเท่าไหร่ มุโคดะก็เริ่มจะจำเหตุการณ์ของเมื่อวานในแต่ละวันไม่ได้ เหมือนกับมันเป็นความทรงจำเมื่อสิบปีที่แล้ว เนื้อหนัง ผมเผ้า เล็บมือของเขาก็ยาวขึ้นในคืนเดียว เปลี่ยนไปเหมือนไม่ใช่มนุษย์ในยุคนี้อีกแล้ว จนครั้งหนึ่งเขาถึงกับตื่นขึ้นมาจากความฝันที่ยาวนานหลายศตวรรษพร้อมพูดภาษาถิ่นที่ไม่มีอยู่จริงในโลก คนไข้ทั้งสองมาเจอกันในคืนหนึ่งที่มุโคดะออกมาเดินเล่นตามห้องโถงโรงพยาบาลเพื่อไม่ให้ตัวเองหลับ เขาเดินผ่านห้องของมามิ ได้ยินเสียงของเธอคร่ำครวญเจ็บปวดถึงความที่เธอกำลังจะตาย เขาเปิดประตูเข้าไปอาจจะเพื่อพูดคุยกับเธอ แต่ด้วยความที่ร่างกายของเขาเหลือความเป็นมนุษย์เพียงแค่สองขาสองแขนเท่านั้น มามิจึงตกกะใจคิดว่ามุโคดะเป็นยมทูตมาเอาชีวิตอาการทรุดหนักลงไปอีก หลังจากที่มุโคดะตื่นจากความฝันครั้งรองสุดท้ายที่เขาแต่งงานใช้ชีวิตกับมามิเป็นพันปี เขาไม่สามารถแยกแยะระหว่างโลกความเป็นจริงและความฝันได้อีก เขาถามหมอคุโรดะอย่างหมดอาลัย คำถามที่หมดสิ้นซึ่งทุกอย่าง

“จะเกิดอะไรขึ้นกับคนที่ตื่นจากความฝันที่ไม่มีที่สิ้นสุด?”

มามิและมุโคดะมีความสลดหดหู่ที่มาจากรากฐานเดียวกัน คือ ทั้งคนไข้ใกล้ตายและคนอมตะทางนามธรรมไม่สามารถครุ่นคิดถึงความตายของตัวเองได้ ความทรมานของทั้งสองเกิดจากสิ่งที่ขาดหายไปจากระเบียบสัญลักษณ์ สิ่งที่ภาษาไม่สามารถเข้าถึง เป็นความล้มเหลวอันเป็นพื้นฐานของอัตตะที่ไม่สามารถอุปมาการหายไปโดยสมบูรณ์ของตนได้ ไม่ว่าตนจะคิดว่ามีเวลาให้พยายามทำมันมากน้อยแค่ไหน จากความหวาดหวั่นของมุโคดะก่อนที่เขาจะเข้าสู่ความฝันนิรันดรครั้งสุดท้าย เราสามารถสรุปรวบการทำงานของเด๊ดไดรฟ์ได้สั้นๆ นิยามหนึ่ง คือ มันเป็นนิรันด์กาลที่ถูกบีบอัดอยู่ ณ จุดใดจุดหนึ่งในเวลา แต่จุดนี้มาไม่ถึงจะดีซะกว่า

มนุษยนิยมปลาด

จ้าวพระยาดันเซนี่เป็นต้นแบบของสูตรเนื้อเรื่องการประพันธ์ประมาณว่าจักรวาลและโลกความเป็นจริงเป็นแค่ความฝันของพระ/เทพจ้าวที่กำลังหลับฝันอยู่ โดยไมเคิ้ล ซิสโก้ เพิ่มจุดหักมุมไม่เหมือนใครเข้าไปในสูตรนี้ ในเรื่องสั้น สิ่งที่ท่านปั้นมากับมือ8Michael Cisco, ‘What He Chanced to Mould in Play’, Secret Hours, (Mythos Books, 2007). มีนิยายอยู่อีกเรื่องหนึ่งที่น่าสนใจคือ Blood Meridian (พิมพ์ครั้งแรกปี 2528 ยังไม่มีแปลไทยและอาจจะแปลไม่ได้) มีตัวละครหนึ่งคือผู้พิพากษาโฮลเด้นที่ชอบไปไหนมาไหนก็จะหยิบสิ่งของที่ไม่มีชีวิตหรือเคยมีชีวิตมาบันทึกในสมุดบัญชีลึกลับ วาดรูปสัดส่วนเหมือนจริง แล้วก็ทุบทำลายมันไม่ให้เหลือซาก เพื่อที่ว่าสิ่งเหล่านั้นจะหลงเหลืออยู่เพียงในสมุดของมันเท่านั้น “สรรพสิ่งใต้หล้าที่ข้าไม่รู้ คือสรรพสิ่งที่ข้าไม่ได้อนุญาตให้มี” เมื่อทุกสรรพสิ่งได้รับคำอนุญาตจากมันให้คงอยู่ได้ นั่นก็เป็นเวลาเดียวกับที่ทุกสรรพสิ่งถูกทำงายไปแล้วจนสูญสิ้น. ตอนจุดสุดยอดของเรื่องตัวละครทั้งสองคือ นายท็อธ กับ นายยาลัธ เติมตัวอักษรที่หัวท้ายชื่อทางกฏหมายของตัวเองที่ทั้งสองใช้มาตลอดชีวิต กลายเป็นชื่อเต็มของ เทพ/พระจ้าวผู้ฝันและผู้ถือสาสน์ของพระองค์ ชื่อสองชื่อนี้เองคือสาสน์ที่มา ณ จุดจบของความฝันนี้ ตัวซิสโก้ไม่ได้สนใจว่าสภาพการจบลงของความเป็นจริงหลังจากการตื่นของอาซาท็อธจะเป็นยังไง แต่เขาสนใจตัวธรรมชาติของการตื่นมากกว่า เขาหักมุมจากเลิฟคราฟท์ที่ลอกแบบพระยาดันเซนี่มาทั้งดุ้นว่า มีเทพ/พระจ้าวองค์เล็กกว่าอื่นๆ คอยเล่นเพลงกล่อมให้อาซาท็อธหลับปุ๋ย ด้วยการเปลี่ยนให้อาซาท็อธจุติออกมาจากจิตไร้สำนึกในรูปแบบของตัวเรียกบ่งชี้ (signifier ในเชิงจิตวิเคราะห์) คือใช้ชีวิตอยู่ดีดีชื่อของตัวเองเติมแต่งนิดหน่อยก็กลายเป็นจุดจบของจักรวาลได้

ภาษาจึงเป็นความตายของเรา มันคือภูมิประเทศทางจิตสำนึกที่ทำให้เกิดความตายขึ้นมาเป็นสภาวะเอกลักษณ์ของสัตว์มนุษย์ ในเชิงจิตวิเคราะห์สิ่งที่แยกมนุษย์ออกมาจากสัตว์อื่นนี้ก็คือระเบียบสัญลักษณ์ที่อนุญาตให้เราครุ่นคิดถึงความตายทางกายของเราได้ เป็นคำสาปที่สัตว์โลกอื่นไม่มีติดตัว คำสาปที่ทำให้มนุษย์จมปลักอยู่กับการอุปมาหาความหมาย ถ้าเราเอาเยี่ยงอย่างตามตำราชาวคริสเตียนที่ว่ามนุษย์ถูกสร้างขึ้นมาตามพระฉายาของพระจ้าว เราก็น่าจะสรุปได้แบบเดียวกับที่โทมัส ลิก๊อตติ นักเขียนมากปลาดวิชชา สรุปจากปรัชญาของปราชญ์เยอรมัน ฟิลลิปป์ เมนแลนเดอร์ ได้เป็นพระจ้าวที่มีฉายาเหมือนกับเรา มีภาษาและถูกแบ่งแยกโดยภาษาที่ตนเองพูดโดยไม่มีผู้ฟังเพราะตอนก่อนกำเนิดจักรวาลมีแต่พระองค์ทั่นเท่านั้น เป็นพระจ้าวที่อาจจะทุกข์ทรมานยิ่งกว่าเราอีก ด้วยความที่พระองค์มีพลังความคิดไม่จำกัดภายในกรอบความเป็นจริงอันคับแคบน้อยนิด ฉะนั้นแล้วเราจะเห็นว่าคำพูดลอยลมติดปากของของพวกลูกศิษย์นีทชี่ที่ว่า ‘พระจ้าวตายไปแล้ว’ เป็นคำพูดที่พูดง่ายเกินไปใครๆ ก็พูดได้ ความเป็นจริงมันไม่ได้สวยหรูขนาดนั้น สิ่งที่เกิดขึ้นจริงๆ แล้วคือ

‘พระจ้าวได้ฆ่าตัวตายไปแล้ว และด้วยว่าพระองค์ทั่นยังไม่หลุดพ้นจากสังสารวัฏ มนุษย์เราจึงต้องรับสืบทอดอัตวินิบาตกรรมมาจากพระองค์’9แปะไว้ตรงนี้ให้ไปอ่านต่อบท การมีตัวนตนคือฝันร้าย (The Nightmare of Being) ในเล่ม ประทุษกรรมมนุษย์ (The Conspiracy Against the Human Race) ของลิก๊อตติ.

ข้าพจ้าวเลยต้องขอไม่เห็นด้วยกับนักจิตวิเคราะห์บรู๊ซ ฟิ้งค์ ผู้เดินทางสายกลางของพวกอเทวะเสรีนิยม เลือกอยู่ฝั่งเดียวกับ ‘ไลฟ์ไดรฟ์ของผู้รับการรักษา เพื่อต่อกรกับเด๊ดไดรฟ์ในทุกรูปแบบ’ และพยายามปัดทิ้งข้อขัดแย้งภายในความเป็นมนุษย์อันศักดิ์สิทธิ์นี้10Bruce Fink, Lacan on Love, (Polity Press, 2016), 147. ถ้าเราปัดทิ้งคอนเส็ปของเด๊ดไดรฟ์แบบนายแพทย์ฟิ้งค์ให้เหลือเป็นเพียงความหมกมุ่นกับอุดมคติทางการเมือง,ศาสนา, และอื่นๆอย่างที่เขาว่า การผูกคอตายของลุงนวมทองในวันที่ 1 พ.ย.2549 ก็จะกลายเป็นสิ่งที่นอกจากจะไม่มีความหมายในทางธรรมชาติความจริงแท้ มันยังกลายเป็นสิ่งที่เราไม่สามารถอธิบายได้ ไม่สามารถแปลงเด๊ดไดรฟ์ไปใช้เป็นเครื่องมือช่วยผู้ป่วยรับมือกับภาวะหวั่นความตาย ดูจากสัมภาษณ์ลุงนวมทองก็จับน้ำเสียงแกได้เลยว่าแกไม่ได้อยากมีหรือชื่นชอบชีวิตในโลกหน้า แต่แกไม่มีอะไรยึดติดอยู่ในโลกนี้แล้วต่างหาก อัตตะที่ตรัสรู้แล้วไม่มีวัตถุให้หมกหมุ่นอยู่ทั้งหลังและก่อนความตาย

สำหรับชาวเราคอมมูนิสต์แล้ว มนุษยนิยมเป็นหัวข้อที่นำมาซึ่งความพิพาท อุดมการณ์ลัทธิเสรีนิยมพยายามจะบังคับใช้มติฉันเป็นเอกเรื่องนิยามของสิทธิมนุษยชนอยู่ตลอดเวลา องค์กรเอ็นจีโอถ้าไม่ได้รับเงินสนับสนุนให้เป็นเครื่องมือทางอำนาจละมุนของรัฐก็เป็นได้แค่องค์กรขอบุญทำทานที่มีดีแค่แก้ปัญหาปลายเหตุ ไม่สามารถคิดโจทย์ทางสังคมภูมิภาคเป็นปัญหาเชิงโครงสร้างภายใต้ข้อบีบบังคับของทุนนิยมโลกได้ มันทำให้มนุษยชาติและความเป็นมนุษย์กลายเป็นสัตว์ประหลาดแฟรงเก้นชไตน์ ถูกสร้างขึ้นจากชิ้นส่วนทีละชิ้น จากข้อเรียกร้องทีละข้อ ไม่ว่าจะเป็นสิทธิการมีที่อยู่อาศัย, สิทธิการเข้าถึงการรักษาพยาบาล, สิทธิการมีงานทำ, สิทธิเสรีภาพทางการแสดงออก และอื่นๆ สร้างล้อมรอบแกนกลางความเป็นมนุษย์ที่ก็ยังคงไม่มีรูปร่าง ว่างเปล่า และไม่ใช่ไม่เกี่ยวข้องกับความเป็นมนุษย์ใดๆ ทั้งสิ้น แหกปากเรียกร้องไปเถอะว่าเราควรจะมีชีวิตที่ดีกว่านี้ ควรจะมีความสุขมากกว่านี้ ข้อเรียกร้องที่เปราะบางในภาษาเชิงบวกของมันเองให้ดังแค่ไหนก็ไม่สามารถเพรียกเสียงครวญครางวิปริตจากภายในที่แว่วเหมือนผีเปรตขอส่วนบุญ ‘ชีวิตและความตายพึมพำอยู่ภายในเรา ถ่างให้หูฉีกยังไงก็จับความไม่ได้’11Thomas Ligotti, The Conspiracy Against the Human Race, (Hippocampus Press, 2010), 224. ความวิปริตนี้คือสิ่งเดียวที่เป็นของเราอย่างจริงแท้ ปฏิเสธมันก็เหมือนกับปฏิเสธแกนกลางความเป็นมนุษย์ (ที่ไม่มีอยู่จริง)

ข้าพจ้าวจึงมีความเห็นว่าถ้าเราจะถกอะไรกันเกี่ยวกับความนิยมมนุษย์ เราควรจะตั้งเด๊ดไดรฟ์อันเป็นสัญชาตญาณ ‘เชิงลบ’ ของสัตว์มนุษย์นี้เป็นหลัก ควรยึดถือพระฉายามนุษย์อันจริงแท้ที่ปรากฏให้เห็นเป็นตัวบรรยายเรื่อง ประชาธิปไตยหลังความตาย ไม่ใช่มนุษย์เพ้อเจ้อผู้วาดหวังวิ่งตามความฝันอันสูงสุด แต่เป็นมนุษย์ที่เหนื่อยจนไม่สามารถวาดอะไรได้ทั้งสิ้น ได้แต่ลากขาตามผีลุงนวมทองของแต่ละคนเอง เผด็จการไหนไม่ว่าจะกรรมาชีพ, นายทุน, หรือศักดินามันก็สามารถนำมาซึ่งชีวิตที่ ‘ดี’ ได้ และด้วยความที่ชีวิตที่ ‘ดี’ นี้มันเป็นสิ่งไม่สัมบูรณ์ตามสภาพทางวัตถุของแต่ละอัตตะและเป็นสิ่งเอกัตนิยมสากล มันก็อาจจะถึงเวลาแล้วที่เราจะเดินแซงผีของลุงนวมทองไป อาจจะถึงเวลาแล้วที่เราต้องมองผ่านการยืนหยัดอัตตะความเป็นกรรมาชีพทางทฤษฎี ผ่านเส้นขอบฟ้าของความเป็นจริงที่เกิดขึ้นจากแรงงานออกไป.

. . .often goodness involves looking forward to a posthumous time when one may look back upon the present with the emotional neutrality and possibly even disinterested and generally-adhesive goodwill of death.

Michael Cisco

Dr. Bondi’s Methods

In the small hours of 20 September 2020 after the MCs had exited the main stage at the Sanam Luang occupation, the first mega protest for thai democracy with turnout numbering in the hundred thousand in recent years, the banned documentary Democracy After Death by director-in-exile Neti Wichiansaen was screened, on a gigantic stage monitor, for the first time in the country since its release in 2016. The film follows the narration of an unnamed and lost soul, a shade of man with no coordinates but the story he tells in which he has no place and whose progress is measured in the increasing degree of Neoliberal globalization characterized by the releases of new iPhone models against the number of coups and Red Shirt casualties in Thailand between 2006 and 2016. Stuck in limbolike landscapes shifting from campfire in oppressing dark to calm seaside to hellish trek across endless sand dunes, the shade constantly addresses and ever chases one that has gone before: an apparition of loong1Loong/Uncle (trans: ลุง; equivalent to ‘uncle’) is a Thai honorific that may refer to an older acquaintance, usually of middle age or above, who is not necessarily genealogically related to the addresser. Nuamtong Praiwal, the taxi driver who on 30 September 2006, after the coup d’état by the military junta under general Sonthi Boonyaratglin, drove his toyota corolla taxi at full speed into a royal thai army M41 Walker Bulldog tank.

For many occupiers that night, this would be the first time that they ever heard of Nuamtong and so were much entranced by his commitment. For some others, his final defiance against the junta’s totalizing remark on his survival from the literal driving towards death — ‘No one is willing to die for their ideology’2Spoken by the junta deputy mouthpiece (of shit) at the time. — already was an ending familiar and so evental that varied interpretations have emerged as a result in both the revolutionary and reactionary consciousness: ‘He was a hero for democracy before his time!’, ‘He shouldn’t have gone and done that. Who’s going to look after his family now?’, and so on. These rationalizations lead us nowhere beyond Nuamtong as a historical object. Subjective facts disconnected from real truth. Here I argue for a weird return to Freud. When considered in isolation, both his concept of death drive and the death of Nuamtong Praiwal are incomprehensible from certain subjectivities; but taken together, and supplemented by a reading of cosmic angst central to the philosophy of weird fiction, they form a picture incomplete in just the right places.

Anastasis: Buddhas Die Twice

Much of the narrative and structure of Democracy After Death directly harks back to Nuamtong’s last words ‘I hope that in the next life there won’t be anymore coup d’état.’3This is Nuamtong’s farewell to his family in the suicide note. Engaging one sided with the dead, addressing the traumatic real that can never answer, the narrator muses at one point how ‘if uncle entered the cycle of rebirth immediately after his death, he would be ten years old by now’. But what exactly is the afterlife, this time after death where the reincarnated Nuamthong may at last get to live the democratic experience foreclosed in his previous life? In a Theory and Psychology article4Kazushige Shingu; Tetsuo Funaki (2008), ‘Between Two Deaths’: The Intersection of Psychoanalysis and Japanese Buddhism, Theory and Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354307087885., Kazushige Shingu and Tetsuo Funaki elaborate on the link between this cycle of rebirth, afterlife and samsara, and what Herr Dr. Sigismund Schlomo Freud refers to as death drive. Reading psychoanalysis alongside the teachings and practices of various japanese buddhist sects, Shingu and Funaki highlight the two basic structural features of an afterlife often glossed over in theistic religions: that it involves another death beyond the physical and that, in the final instance, its ex-sistence relative to the two deaths is not chronological. One facet of death drive can be understood through the subject’s dynamics within this structure.

We can well imagine the following everyday Leninist scenario involving the salaryman:

a senior civil servant finds himself caught between two colleagues debating the excessive use of force by the state to disperse a crowd of protesters the day previous, to which the senior throws up his hands, shakes his head and says, “Look, we’re not supposed to talk politics in this building while wearing this uniform. I’ve got a family who rely on my income and benefits, and I don’t want to ruin it for them or lose my pension. After I retire I’m going to play as much pool as I want and that’s all that matters.”

The psychoanalytic death drive consists in this indefinite postponement and repetition — that is, the senior’s placement beyond a future point in time of a period in which he could at last live life on his own terms and the hobby or activity that sustains this structure in the eternal present5Perhaps today we can find some of the most acute manifestations of death drive in the Hikikomori social-hermit phenomenon endemic in the late capitalist urbanscapes of East Asia. Contradictions in such cases are able to present themselves so sharply primarily because the subject has opted out of a certain process of reproduction of labour power: a complete retreat from social life is required, as it were, so that some kind of life could be imagined at all.. Freud regards the pleasure-principle, the drive towards a pleasurable resolution of the subject’s inner tensions, as ultimately subserving ‘a certain function . . .but we note that the function so defined would partake of the most universal tendency of all living matter — to return to the peace of the inorganic world.’6Herr Dr. Sigismund Schlomo Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Section 7. Those familiar with the work of Robert Pirsig may recognize this inherent tendency as the “immoral” atavistic descent from the biological/organic to inorganic pattern. How does such a totalitarian concept as the metaphysics of quality resolve this contradiction? Following this particular logic, we can see then that the retiree’s life the senior civil servant imagines for himself is actually not the object of his pursuit as such, that to attain a life of our own means in truth to attain a life in which we could start coming to terms with our own physical first death, whether we are aware of this process or not. And there is no guarantee that the structure will not repeat itself in some other outwardly different form — finding religion in old age, taking up a new daring pastime, and so on — even after the senior manages to reach retirement without a hitch.

This coming to terms with our own first and, objectively speaking, only death is virtually the goal of all religions. But it is in the buddhism as originally taught by Gautama Buddha, the religion that seeks to help the subject free itself from the language of death’s desirability/undesirability, that the structure of afterlife is most accurately depicted. In a supremely Lacanian maneuver, Gautama Buddha achieved nirvana, the second death of suffering caused by the fact of our mortality, before passing away, both reversing and collapsing conventional chronology. The hereafter is finite and ends before it can begin.

Democracy After Death is not a story of Nuamtong’s afterlife but of our own, his second death having already been achieved and discernible at least in his resigned acceptance of reincarnation. The narrator and the audience both are the ones still caught in samsara, awaiting the coming of democracy like the civil servant awaiting retirement, sustained by some perpetual repetition.

Subjective Immortality

The reader may now ask at which point did Nuamtong effectively attain enlightenment? The monumentality of his driving towards death seems to suggest that he either attained it prior to getting in his taxi that day or after surviving the crash. I do not think that the exact location of this moment matters overmuch, since a subject caught in death drive experiences the present as an immortal, i.e. their afterlife lies always in an indefinite future. Contrary to what is taken for granted in popular psychologic ideologies, death drive is anything but violent. It operates beyond, not antithetically to, the pleasure-principle; when pleasure has been exhausted what remains is not violence but melancholy. We should even resist reading violence in symbolic suicide — and I’ll show later that suicide can only be symbolic — since this is how the Thai state characterizes Democracy After Death and justifies its ban to avoid an encounter with Real trauma.

Similarly, by reading beyond the genre’s horrific imagery and traditional horror tropes, can we get at the true character of contemporary weird fiction; and this applies perhaps most of all to the manga of Junji Ito, whose visual grotesqueries may prove too much for some weird fiction enthusiasts, especially the Lovecraft purists7The debate on the merit of Ito’s visual presentation belongs to the larger nascent discussion on what weird fiction is in the context of thai supernaturalism. At the 2020 annual Lovecraftian Thailand meeting in August, one of the often cited rules of thumb for telling Lovecraftian horror apart from conventional horror is that the former does not rely on overtly grotesque visual scares. The rule is obviously inadequate. The point is not that the images are too much, but that they are never quite up to the task despite the shock factor. . Known for such frightening, stomach-churning, anxiety-inducing8What makes Ito’s work so effective, in my opinion, is that it contains all three elements related to neuroses briefly discussed in Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle: apprehension, in that every turn of the page is potentially a window into an everyday world bepopulate by horrors without antecedent; fright, in that the reader, though expectant, is never prepared for the revelations; fear, in that the revealed monstrosities do not lose their horror momentum even so divested of their earlier mystery. series as Uzumaki and Gyo, the height of Ito’s weird originality can be found in the short story Long Dream from The Junji Ito Horror Comic Collection, Vol. 9. In Long Dream, neurosurgeon Dr. Kuroda treats two patients: Mami, afflicted by a death anxiety more severe than her illness warrants, and Mukoda, whose subjective experience of time’s passage inside a dream seems to grow longer with each passing night. Mukoda at first experiences one night’s dream as lasting roughly one year. As this subjective time grows exponentially, and the content of his dreams more outlandish, he soon struggles to recall events of the previous waking day. His physical appearance grows hideous and inhuman, and he once wakes from a century-long dream speaking in dialects of nonexistent peoples. The two patients cross paths when one night Mukoda walks the hospital corridors to keep himself awake. He enters Mami’s room as he passes and hears her agonizing over her inevitable death. But because of Mukoda’s barely human visage, Mami thinks he is the grim reaper and suffers a breakdown, after which her death anxiety considerably worsens. After waking from a thousand year-long dream in which he is married to and living happily with Mami, Mukoda, no longer able to distinguish between transient reality and illusions that last countless lifetimes, voices his greatest fear,

‘What happens to the man who wakes from an endless dream?’

In their parallel, Mami and Mukoda share a fundamental melancholy: neither the dying patient nor the subjective immortal can contemplate their own end. Their suffering arises out of language’s inadequacy, the fundamental failure to metaphorize the disappearance of the subject itself, no matter how much time they may think they have. And we can perhaps derive from Mukoda’s apprehension an understanding of the practical operation of death drive: eternity in a single finite moment is okay so long as it never arrives.

Towards a Weird Humanism

In his short story What He Chanced to Mould in Play9Michael Cisco, ‘What He Chanced to Mould in Play’, Secret Hours, (Mythos Books, 2007). Also, see Cormac McCarthy’s seminal novel Blood Meridian (1985) for the character judge Holden who in his ledger sketches and records lifeforms and objects he comes across in his journey, then destroys the very things the material properties of which he has inscribed so that their existence may consist only in the written words of his accounting: ‘Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent.’ The moment all of creation receives his consent is also the selfsame moment it no longer is., Michael Cisco adds a unique twist to the Dunsanian eschatological formula of reality being nothing more than a dream of a sleeping god. The denouement sees the two characters Mr. Thoth and Mr. Arlath completing the names of the dreamer and the dreamer’s messenger, thereby bringing the dream to its culmination, by simply adding a few letters to the legal names they have harmlessly borne all their lives. Cisco is not here concerned with the outcome of Azathoth’s awakening, that is, the end of reality itself, but with the nature of this awakening. Instead of the usual trope in which lesser gods lull Azathoth with music — a possible mechanistic materialist metaphor for the inevitable triumph of entropy — Azathoth in What He Chanced arrives out of the unconscious as a signifier.

Language, then, is our death. The advent of consciousness brings a condition unique to the human creature. Psychoanalytically speaking, what distinguishes the human is the symbolic order which allows us to contemplate our own somatic death, to fumble evermore with inadequate metaphors, a blessed impossibility for other animals who function only at the level of images. And if we are to take seriously the christian doctrine that we were created in god’s own likeness, we should come to the same conception that Thomas Ligotti, master weird fictioneer, reads from Philipp Mainländer’s philosophy of a god as articulate, as alienated, as agonized as we are by the mere existence of his ability to think infinitely in a finite reality. Seen thus, the Nietzschean platitude God is Dead appears to oversimplify the truth of the matter:

God has killed himself. And from him, caught as he is in endless samsara, we have inherited suicide.10 See Ligotti’s discussion on Mainländer’s Will-to-die in The Nightmare of Being chapter in The Conspiracy Against the Human Race.

This is why I must disagree with Bruce Fink who takes the middle road of the liberal atheist, sides decisively with ‘the patient’s life drive against death drive in all its forms’, and tries to summarily sweep this aspect of human contradiction, this divine inheritance, under the rug.11Bruce Fink, Lacan on Love, (Polity Press, 2016), 147. Fink, who reduces death drive to fixation on political; religious; and other ideals, would struggle to explain the conditions of Nuamtong’s suicide on 1 November 2006, and would dismiss the drive’s potential as a coping mechanism. It was clear from the interview that Nuamtong did not feel anything close to favoring a next life; he simply felt no particular attachment to this one. The enlightened subject has no object to fixate on in the course of imminent death.

For good honest communists, humanism is a contentious subject. Liberal ideologies attempt to enforce a consensus on human rights at every turn; ineffective if not downright hypocritical NGOs tackle ‘humanitarian’ crises like overfunded charities, unable or never intending to address local contradictions within global capitalism. Humanity is jerrybuilt from egalitarian demands — right to housing, right to healthcare, right to work, right to speak freely, and so on — around a core of being that remains undefinable, nonhuman. The loud sensible cry for the right to fully live, the right to enjoy life, rendered vulnerable by its own positive language, drowns out a fundamental madness that begs to be heard. ‘The living and the dead jabber inside you. You cannot understand them.’12Thomas Ligotti, The Conspiracy Against the Human Race, (Hippocampus Press, 2010), 224. This madness alone is ours. And to deny it in ourselves and in others is to deny the human essence, which of course does not exist.

Thus, any meaningful discussion involving humanism, I think, should proceed from this ‘negative’ aspect of the human instinct. Should proceed from the image of the real human, the narrator of Democracy After Death. Not any chaser of dreams driven onward by hopes, but a despairer after some Nuamtong of our own. Any dictatorship — feudal, bourgeois, proletarian — can give anyone a good life. And just as the good life is in particular relative to the subject’s material conditions and is in a sense universally solipsistic, then maybe it’s time for us to overtake Nuamtong’s ghost. Maybe it’s time to look beyond the theoretical affirmation of proletarian subjectivity, beyond the reality of labour itself.

ดีโยน ณ มานดารูน |

Dion de Mandaroon

ดีโยนทำงานประจำเป็นทหารเลวในเหล่าทัพหนึ่งของกองทัพไทย ชอบอ่านและเขียนเกี่ยวกับวรรณคดีแนวปลาด (ปลาดคดี) ถ้าเจอกันที่ม๊อบก็ชวนคุยเรื่อง เอชพี เลิฟคราฟท์ หรือวิทยาศาสตร์อมตะสำนักมาร์กซิสซึ่ม-เลนินนิสซึ่ม-เหมาอิสซึ่ม ได้

Dion barely works as a soldier for a branch of the Royal Thai Armed Forces. He reads and writes about weird fiction. If you see him at protests, ask him about H.P. Lovecraft or the immortal science of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism.

ดีโยนทำงานประจำเป็นทหารเลวในเหล่าทัพหนึ่งของกองทัพไทย ชอบอ่านและเขียนเกี่ยวกับวรรณคดีแนวปลาด (ปลาดคดี) ถ้าเจอกันที่ม๊อบก็ชวนคุยเรื่อง เอชพี เลิฟคราฟท์ หรือวิทยาศาสตร์อมตะสำนักมาร์กซิสซึ่ม-เลนินนิสซึ่ม-เหมาอิสซึ่ม ได้

Dion barely works as a soldier for a branch of the Royal Thai Armed Forces. He reads and writes about weird fiction. If you see him at protests, ask him about H.P. Lovecraft or the immortal science of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism.